Dietary Management

People with PWS have a high risk of becoming obese due to the high fat to muscle ratio causing reduced energy expenditure and the need for reduced energy intake, whilst the altered appetite regulation and food reward signalling can make a person obsessive about food and likely to be feeling hungrier than others. Imposing a strict diet on someone with hyperphagia can be difficult, but without effective dietary management, people with PWS will rapidly become morbidly obese and suffer serious health issues that will impact the quality and length of their life.

Understanding nutritional phases in PWS

In the past, PWS was described as a 2 stage syndrome – failure to thrive followed by hyperphagia. It is now known that the changes in appetite and weight gain are more gradual and complex. Parents of children diagnosed in infancy have the opportunity to instil diet modifications and healthy eating habits well before the child’s appetite or interest in food increases. As a result, when phase 3 begins, it is often less severe in families who have implemented early intervention measures.

Phase Ages Characteristics

1a 0 – 9 months Hypotonia with difficulty feeding and decreased appetite

1b 9 – 25 months Improved feeding and appetite; growing appropriately

2a 2.1 – 4.5 years Weight increasing without appetite increase or excess calories

2b 4.5 – 8 years Increased appetite and interest in food, but can feel full

3 8 years – adulthood Hyperphagic (abnormally increased appetite); rarely feels full

4 adulthood Appetite is no longer insatiable (only very few adults)

WHAT IS THE BEST DIET FOR PWS?

There is no single, correct way of feeding a person who has Prader-Willi syndrome – different approaches can work for different individuals and families. However, there are several key elements that should be part of any dietary management plan for PWS.

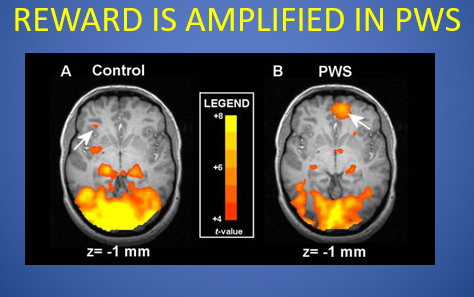

- As much as possible – eliminate sugar. Brain scans show that sugar is even more rewarding to people with PWS than the rest of us, and families usually find both behaviour and weight management improve when it is eliminated or significantly reduced. Sugar also does very little to curb appetite and can increase a possibly already heightened diabetes risk. Artificial sweeteners should also be avoided. They have fewer calories, but will still have the sweet taste which drives reward, and affect metabolic signals, i.e. the calories the brain associates with sweetness are not received, so it still craves them and hunger is not satisfied.

(As people can be conditioned to favour particular types of food during childhood, many parents opt to completely eliminate sugar whilst it’s possible to do so because this may help their child to make better food choices when older. If sweet foods are occasionally allowed later on, it is best they are seen as treats which are only allowed at planned times.)

- With the help of a dietitian, regularly review your child’s weight and daily nutritional intake and consider whether their energy intake needs to be adjusted. An approximate target amount of calories per day may be recommended (often 50-70% of what is typical for age from phase 2a).

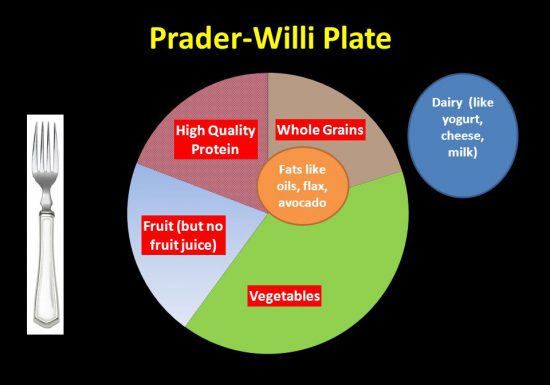

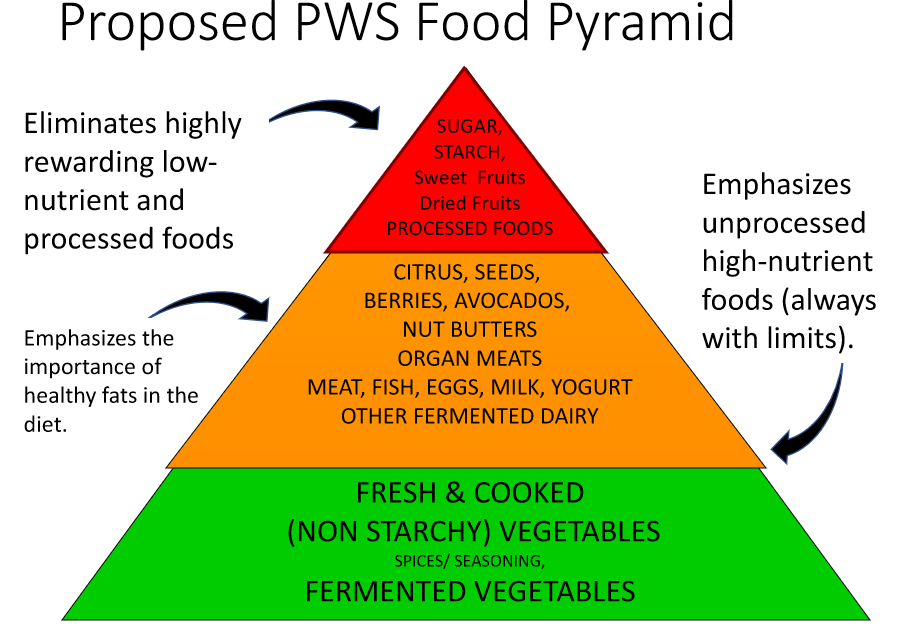

- Aim to provide your child with a well balanced, but reduced carbohydrate diet. International guidelines advise typical diets contain 45-65% carbohydrates, but in PWS it is advised this is reduced and an approximate recommendation is 30% protein, 40% complex carbs and 30% healthy fats. Focus on non-starchy vegetables and high quality protein – reduce all processed food and, in particular, processed carbohydrates. Avoid empty calories. Drinks should be water or milk for children. Sweet drinks and artificially sweetened diet drinks should be avoided. Develop a small set of meals and snacks on rotation and become familiar with what the appropriate portion size looks like. Use the same plates or weigh if needed. Your child’s palm of hand is a good measure of an appropriate carbohydrate serving size.

- Aim for at least 30 minutes of exercise per day – more if the person with PWS is overweight.

- Set up rules and routines around food, such as only eating at the table and set meal times. Decide as a family how you will manage out of the ordinary events such as birthday parties. Consistency is key. Make sure the person with PWS understands that food will only be available at meal times. This may require locking cupboards and fridges. The ‘Food Security’ method works well, both for weight management and for reducing preoccupation with food and associated anxiety.

It is also a good idea to teach the person with PWS about nutrition and for them to know what is good and bad for their body.

We have detailed resources that cover dietary management, food security and locking options. Request as a hard copy or download here:

These are the principles of ‘Food Security‘ developed by the Pittsburgh Partnership:

NO DOUBT

A predictable menu sequenced in a predictable routine (focus on sequence rather than time) allows the person to relax and think less about food.

+ NO HOPE

No unplanned extras or opportunities for access to food. Chances to obtain food cause stress. Modify measures as food seeking varies and fluctuates.

= NO DISAPPOINTMENT

The person only has expectations that will be reliably carried out. No other expectations have been raised so there is no disappointment when these are not realised or fulfilled.

Macronutrients Matter

In the past, most families were instructed to follow a low calorie, low fat diet. While calorie control remains important, in recent years the focus has turned to the macronutrient (protein, carbohydrate, fat) balance in the diet. It is now recommended to reduce or eliminate sugar intake and focus on good quality protein, vegetables, and to include some good fats in the diet. Read food nutrition labels rather than just calorie content and check packaging claims, i.e. ‘no added sugar’ does not mean no natural sugars and ‘low fat’ foods may contain added sugars or sweeteners. As more is now known about the effects of sweet foods on the brain and the increased risk for insulin resistance in PWS, it is recommended that traditional ‘diet’ foods, which are still sweet, should be avoided. It is also easier to monitor macronutrient intake by sticking to simple foods rather than those with a large number of ingredients.

In 2013, Dr Jennifer Miller and her team at the University of Florida published a study that compared a group of children on a calorie controlled diet vs children on a calorie controlled diet that was lower in carbohydrates. They found that children who followed the lower carbohydrate diet weighed less and had less body fat. The recommended diet was:

45% carbohydrate, 30% fat and 25% protein, with at least 20g of fibre per day. This is similar to the Mediterranean Diet advocated by expert dietitian, Melanie Silverman, which was recently successfully trialled at Latham Centers in the USA.

The relative proportions of foods in these diets can be visually represented by the Prader-Willi plate graphic from dietitian Melanie Silverman, and the Prader-Willi food pyramid proposed by Dr Linda Gourash from the Pittsburgh Partnership which places additional focus on gut health by proposing the inclusion of fermented foods. (Note that the red foods in the pyramid are not recommended and should be avoided where possible.)

What about very low carb / high fat diets?

Recently there has been interest in the PWS community around very low carbohydrate/ high fat diets – the Modified Atkins and Ketogenic diets. Some families found that energy, behaviour (particularly food seeking) and weight management improved on these diets. In 2016, TREND Community supported ten families to transition to a ketogenic diet and record their experiences in their online database. TREND aims to “turn anecdotes into evidence” as it is very hard to get clinical trials up and running in the rare disease community. The families that lasted for the whole six month trial found it very beneficial and the results are summarised in the White Paper. Research into these diets is still ongoing with several clinical trials underway, but to date, nothing has been published.

It is important to consider that whilst a child is growing, good, complex carbohydrates are needed for growth and muscle building. If there is insufficient carbohydrate in the diet, the body will use protein and fat to grow and the body will not make muscle. This, in turn, makes it more difficult to exercise and be physically active.

Very low carb/ high fat diets will induce ketosis, where the body preferentially burns fats. It is important to have medical supervision from a dietitian and paediatrician who can order and interpret the regular blood tests required. Until the benefits and risk of these diets for PWS have been scientifically determined and any long-term risks considered, we would advise caution.

What about adapting diet for gastro-intestinal issues?

An article published in 2016 has recommended a soft, lower fibre diet for people with PWS. This is contradictory to the high fibre advice normally given for preventing constipation, a common problem in PWS. This new recommendation is a result of new concerns about gastroparesis (slow stomach emptying), bowel obstruction, swallowing dysfunction and high choking risk. If you have concerns about any of the above issues, we would recommend a medical evaluation and dietary adaptation may be advised. To aid digestion, all people with PWS would benefit from regular exercise and drinking water during and between meals to make up for low saliva production. You can also aid digestion by providing more frequent smaller meals and adding probiotic foods to the diet.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

- A reduced-energy intake, well-balanced diet improves weight control in children with Prader-Willi syndrome – J. L. Miller, C. H. Lynn, J. Shuster, & D. J. Driscoll, 2012.

- Exercise and Physical Activity for children with Prader Willi Syndrome: A Guide for Parents and Carers – Kirsty Reid and Peter SW Davies, Children’s Nutrition Research Centre, University of Queensland

- New Concepts in Nutrition: PWS Nutrition Revised – Linda M. Gourash, MD, Pittsburgh Partnership, 2017

- The Mediterranean Diet and an Overview of Low Carb Diets for PWS – VIDEO CLIPS from Melanie Silverman’s presentation at the FPWR 2018 conference. Full video available here.

- Optimal Nutrition in Prader-Willi Syndrome – Slides by Melanie Silverman MS, RD, IBCLC.

- Nutrition Tips for PWS – VIDEO of Hannah Stahmer, MS, RDN, LD, presenting at The Mac Pact PWS Conference, 2017

- Overview of Diets explored in the TREND Community PWS Diet Initiative (also includes ‘The White Paper’ review, 2016, and diet resource sheets by TREND and The Charlie Foundation.)

- Rethinking our Approach to Diet and Nutrition for the Person with Prader-Willi Syndrome (Gastrointestinal Health) – Article by Barb Dorn R.N., B.S.N., Kate Beaver M.S.W. and Margaret Burns R.D., 2016.

- Hidden Gut Issues (Choking & Gastroparesis Concerns) – By Barb Dorn, RN, BSN, Kate Beaver, MSW, Kathy Clark, RN, MSN, PNP, and Margaret Burns, RD

- Prader-Willi Syndrome: The Behavioral Challenge – A Brief Summary for Professionals (FOOD SECURITY) – Drs Gourash and Forster, Pittsburgh Partnership, 2016

- Food Security The TRAIN Model – VIDEO of Dr J Forster presenting at the 3rd Asia-Pacific PWS Conference, 2015

- Food Security Checklists – Janice L. Forster, MD & Linda M. Gourash, MD, Pittsburgh Partnership

- What’s Wrong with Food Rewards in PWS? – Drs Gourash and Forster, Pittsburgh Partnership, 2015

- Food is Never OK in the Classroom – from The Gathered View (ISSN 1077-9965), PWSA(USA), 2006

- Increase Success in the Workplace: Limit Access to Food – by Lisa Graziano, Prader-Willi California Foundation

- Beyond The Diet – For the Dietitian – by Janalee Heinemann, from The Gathered View (ISSN 1077-9965), PWSA(USA), 2005

- Meals and Snack Ideas for PWS – by Melanie Silverman MS, RD, IBCLC.

- PWS Recipe Exchange – A Facebook group for parents and carers to share tips and recipes.